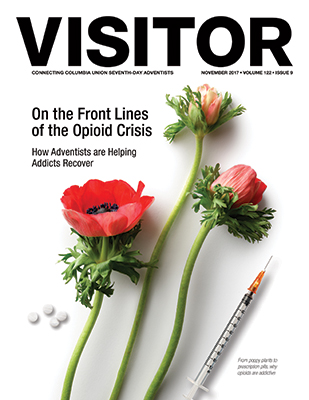

November 2017 Feature: On the Front Lines of the Opioid Crisis

Story by Tamaria L. Kulemeka

The opioid and heroin epidemic is crippling communities across the nation, leaving health officials and providers, coroners, law enforcement and churches scrambling to respond to and combat this widespread crisis.

Bonnie Franckowiak, professor and coordinator of the Master of Science Nursing Program at Washington Adventist University in Takoma Park, Md., says, “The use of opioids in this country is staggering. It’s huge, and it’s growing all the time; we don’t seem to have a handle on it at all,” she says. “In 2012, 259 million prescriptions were written for opioids, which is enough to give every American adult their own pill box.”

Bonnie Franckowiak, professor and coordinator of the Master of Science Nursing Program at Washington Adventist University in Takoma Park, Md., says, “The use of opioids in this country is staggering. It’s huge, and it’s growing all the time; we don’t seem to have a handle on it at all,” she says. “In 2012, 259 million prescriptions were written for opioids, which is enough to give every American adult their own pill box.”

Franckowiak notes, “Four out of five new heroin users first started out on prescription painkillers.” She adds that 85 percent of opioid users get their pills from a friend.

Since prescription drugs are too costly to purchase on the streets after prescriptions run out, those who develop addictions often turn to heroin to relieve their symptoms and discomfort, she says.

Unfortunately, addiction leads to accidental overdoses, which Kettering Adventist HealthCare’s Kettering Medical Center staff in Ohio has seen at alarming rates in communities “from urban to suburban and rural,” says Nancy Pook (pictured below), M.D., medical director of the hospital’s Emergency Department.

The hospital serves five counties in the greater Dayton and Cincinnati areas, including Montgomery County, which recently clinched the title as the county with the highest number of drug overdose deaths per capita in the U.S. Pook says this record was set June 19 when the number of deaths eclipsed the total of all of 2016.

The hospital serves five counties in the greater Dayton and Cincinnati areas, including Montgomery County, which recently clinched the title as the county with the highest number of drug overdose deaths per capita in the U.S. Pook says this record was set June 19 when the number of deaths eclipsed the total of all of 2016.

“In general, EMS personnel are responding to an increased number of overdose calls, and many of the patients are [repeatedly] being treated with Narcan [an opioid antagonist reversing the effects of opioids]. The impact of fentanyl products (painkillers) in our community has triggered this excessive death rate, in large part,” Pook explains.

“This tragedy is a serious and complicated problem for our culture, and our caretakers must be both diligent and attentive, as well as resourceful, avoiding rescuer fatigue themselves due to the negative social consequences surrounding the poly-drug epidemic,” she adds.

All Walks of Life

All Walks of Life

Opioid addiction is not discriminatory; it affects people from all walks of life.

“While the typical overdose patient is a young, white adult, often from a middle-income community, all ages and races and socio-economic groups are affected,” Pook says. “We see pregnant women with active addiction, babies born addicted, toddlers in foster care due to addiction’s consequences, teenage users and adults through the end of life using a variety of illicit drugs or buying drugs off the street. We see homeless people, working adults and professionals. Often we see a family in crisis due to the ravages of addiction and its consequences. Addiction is blind to race, socio-economic class, church affiliation and good intentions.”

Pook adds that people with drug dependencies often start as good people with good families who attend good schools.

One of the major factors escalating the crisis in Kettering Medical Center’s coverage area is location. Pook says Dayton is at the crossroads of two major U.S. interstates: Interstate 75 travels north and south, while Interstate 70 travels east and west.

“We know our community is targeted by drug cartels for trafficking, based on input from the Drug Enforcement Administration,” she says.

This epidemic is absolutely changing nursing instruction and care across the board, says Franckowiak.” It doesn’t matter where you work—in schools, the ER or obstetrics unit—wherever nurses work, they’re bound to encounter people who have a problem, or use or are at risk of using or becoming addicted,” she says.

WAU’s nursing program is teaching students how to screen for addiction and abuse and educating them on how to refer those who may be addicted.

Minnie McNeil, recently retired Adventist Community Services/Disaster Response director for Allegheny East Conference (AEC) and the Columbia Union Conference, says that the crisis also affects family members of addicts, especially when both parties don’t feel comfortable sharing their struggles. “Our prayer is that our churches will be safe-havens where we can ban together in prayer, yes, but also that we can extend our referral sources and support families so they feel able to talk about it so that those addicted can get the help they need,” she says.

The Forgotten Ministry?

“[The church] is supposed to be a hospital, but we’re not all ready to address the sick,” says James Jackson, AEC’s coordinator for Adventist Recovery Ministry (ARMin), and a member of the Mount Olivet church in Camden, N.J., who spent 20 years under the influence of alcohol and other drugs. After being “restored to sanity” and getting clean, he worked as a counselor and retired as a clinical supervisor for an agency that provided mental health and substance abuse services in the city.

“We’re good at feeding them, but we still don’t have a place where someone going through something can get help or referrals,” Jackson says. “The amount of drugs and prostitution in the streets is a result of hurt people. Hurt people hurt people; and we have no answer for that in our churches.” But he adds, “ARMin could be the answer.”

“We’re good at feeding them, but we still don’t have a place where someone going through something can get help or referrals,” Jackson says. “The amount of drugs and prostitution in the streets is a result of hurt people. Hurt people hurt people; and we have no answer for that in our churches.” But he adds, “ARMin could be the answer.”

Formerly known as Regeneration, the purpose of ARMin is to address addiction in a wholistic manner, not just focusing on drugs, alcohol and addictions, but on all compulsive behaviors and underlying problems, Jackson says.

Their meetings, patterned similarly to the Alcoholics Anonymous model, use a modified 12 steps, 12 traditions and 12 concepts and provide a safe, confidential atmosphere of support where people can learn how to find freedom from their unhealthy habits.

Jackson says ARMin is not as visible as it should be in churches, and in many churches, it’s nonexistent. “I would like to see that it becomes a household word in churches and not a forgotten ministry,” he adds. “Once people become a deacon or elder in the church, they don’t like to be exposed as an addict, so we have a lot of members, but a lot don’t participate in the program.”

In the Trenches

Darcel Harris is thankful for the success her 12-step group, patterned after the Regeneration model, has experienced for nearly three decades. Harris, a middle school Language Arts teacher, psychology professor and author in Westminster, Md., says the group grew out of Chesapeake Conference’s Westminster (Md.) church, where she is a member. Today they meet every Friday night and during a branch Sabbath School service called True Vine. They also operate a non-profit called Grow, which enables them to provide resources and minister to the needs of homeless people, drug addicts and the less fortunate in the community.

Harris, a recovering alcoholic and cocaine addict, echoes that the group does not just deal with drug and alcohol addictions, but addresses 13 primary issues, including overeating, rage and depression. “The same neglect an alcoholic gives his or her children [is the same as] a workaholic, so we look at addictions, behaviors and choices, not just alcohol and drugs,” she says.

Harris, a recovering alcoholic and cocaine addict, echoes that the group does not just deal with drug and alcohol addictions, but addresses 13 primary issues, including overeating, rage and depression. “The same neglect an alcoholic gives his or her children [is the same as] a workaholic, so we look at addictions, behaviors and choices, not just alcohol and drugs,” she says.

Harris also says the reason it is so hard to treat people for drugs or heroin is because no one ever gets to the root of the problem. “Once you get rid of what the real thing is, the obsession is gone,” she adds. “For example, if you’ve been sexually molested, I don’t care how many counselors you go to, you will keep going back to your addictions; the craving or the need for it came from the pain. … If God can heal you from that pain, then that’s how you get free from addictions.”

The work Harris is doing in the community is making a “huge impact,” says Robert Martinez, Westminster church pastor. While there is a visible drug problem in the city, Martinez says he doesn’t deal with the issue much, but when he’s with Harris, it’s right in his face, and he prays with people who are high.

“[Harris] is so practical,” he says. “A lot of our Adventist churches aren’t practical. [It seems] we aren’t living in the same world as most people. We don’t relate to their needs. … We’re good to the people who are like us. … She is right there with them, helping them.”

On the Front lines

Norman Carter, a member of Allegheny West Conference’s Temple Emmanuel in Youngstown, Ohio, is also on the frontlines of the drug crisis.

“[The opioid crisis] is a beast that’s been unleashed. … In order to stop it, you have to stop drugs, and we know that is not going to happen. I think that all we can do is be prepared to provide services to those in need,” says Carter, who kicked his crack cocaine habit nearly eight years ago, and three years ago founded the Carter House, a transitional residential program in Youngstown.

The not-for-profit organization operates four houses with 26 beds for alcoholics and substance abusers in recovery and who need to transition back into the community. Residents live in the Carter House anywhere from 90 days to a year.

The not-for-profit organization operates four houses with 26 beds for alcoholics and substance abusers in recovery and who need to transition back into the community. Residents live in the Carter House anywhere from 90 days to a year.

“I had no idea the opioid epidemic was going to be what it is today; I was just providing the piece to the puzzle that was so important to helping me in my process,” he says.

Carter, who started selling drugs right out of high school and soon began using those drugs, graduating to crack cocaine at age 30, said his second lease on life came after being arrested for stealing from Wal-Mart to buy drugs. Instead of being charged with a crime, Carter was given the option to enter a drug program and have the charges dismissed, as long as he completed the program.

Carter completed his 60-day treatment program and moved into a transitional facility like the one he now runs. He eventually returned to his Seventh-day Adventist roots and sought the church for support. Pastor Bryant Smith and the church got on board with the Carter House, supplying them with food and clothes, conducting Bible studies for residents and praying for the ministry.

Today Carter strives to love those trying to rebuild their lives until “they can love themselves.” He says there are days when those in recovery relapse, but this just makes him work harder for those who have yet to come through the doors.

Photos by Darren Bullock, James Bartosik, Tijuana Griffin and Kevin Cameron

Read and share these articles from the November 2017 Visitor!

Read and share these articles from the November 2017 Visitor!

Add new comment