Unmapped: Doubt, Disconnection and Disillusionment

By Becky St. Clair

By Becky St. Clair

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the subjects and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of the Columbia Union Conference or Visitor staff.

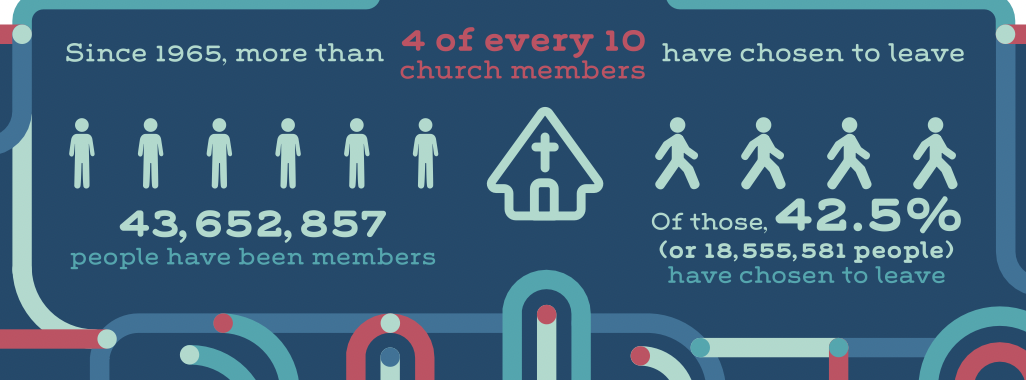

According to official Seventh-day Adventist statistics, since 1965, four out of every 10 members have left the church.

Choosing God ... and Adventism

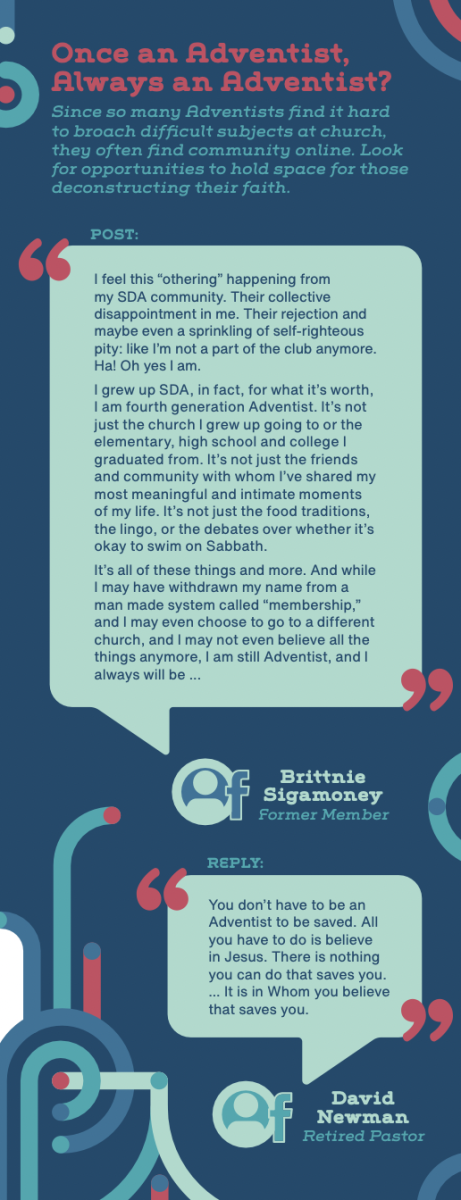

Brittnie Sigamoney grew up in Florida with a large backyard full of orange trees among which she spent many happy hours. She was part of a traditional Adventist family, and her mother taught her she could talk to Jesus anywhere, anytime. “I never had an imaginary friend because I always had Jesus,” she recalls.

As she got older, Sigamoney began to question if that connection with Jesus was real. A formative moment came when she was 12 and heard Jesus say, Yes, that was real! We played in the orange trees and caught bugs together, and I had fun with you. She concludes, “I have a long history of a personal relationship with Jesus.”

Sigamoney spent two years with her family as missionaries in India and attended Adventist schools, including Washington Adventist University in Takoma Park, Md. Over time, however, she became disillusioned with the church. She felt being a member of the church added little to her life and was, in fact, being used against her to benefit the church’s agenda.

And so, Sigamoney withdrew her name from membership out of protest.

“My ‘spiritual gift’ is to be questioning,” Sigamoney says. “To be outspoken. I felt I had more power in withdrawing my membership than in keeping it,” she says.

Removing her name, however, does not mean she has removed herself from God. She and her family now attend a Sunday-keeping church. “Choosing Jesus is a different thing from choosing Adventism,” says Sigamoney. Having been brought up to differentiate people from God, she adds, “God is not Adventism. Adventism is just people doing the best they can, and we all make mistakes.”

All About the Rules

Having a personal relationship with God, but not regularly attending church on Sabbath is not uncommon with many Adventists in Generation X—those born between 1965 and 1980—and, in some cases, the Xennials—those born in the transition years between Gen X and Millennials—1981 through 1996.

“I can’t imagine a day when I would remove my name from the ‘books.’ Being an Adventist is in my blood,” says Paul Bergmann, an Adventist who lives in New Jersey. “I cherish the lifelong relationships I’ve built through my Adventist education and will always be grateful for the Christian foundation I have. But I have not raised my girls the way I was brought up.”

Some Gen Xers recall growing up in the church as being a set of rules, and if they didn’t follow those rules, there was no place for them in heaven.

“I know our parents, Bible teachers and pastors were well-meaning,” Bergmann concedes, “but all we heard was, ‘You can’t swim on Sabbath, eat meat, wear jewelry or go to the movies.’ The focus was on what we could or could not do—like God was waiting for us to fail. Later in life, I learned God is, in fact, a forgiving and understanding God who just wants us to be close to Him.”

Nowadays, many Gen Xers find themselves back at church—a result of them taking their children to Sabbath School—and many want their children to have an Adventist education. However, they follow their own version of Adventism, which focuses less on cultural customs and more on prayer, trust and living in God’s grace.

Finding a Church That Loved Me

Finding a Church That Loved Me

Belkis Rondon grew up in Venezuela and was introduced to Adventism by a friend at the age of 9. Later, at a spiritual retreat for Adventist young adults, Rondon met the man who would become her husband. The marriage fell apart not long after it started, and Rondon learned a painful secret her husband was harboring—one that others had already known.

“The whole church knew, even the pastor,” Rondon says. “My husband used me, and the entire church let him do it.”

Despite her pain from betrayal by her local church, Rondon still felt Adventism was the right religion for her. She prayed regularly to God, saying, If you want me to come back to church, You need to lead me to an authentic church.

God replied, and she followed His direction to a loving Brazilian church in Richmond, Va., that immediately made her feel at home.

Today, Rondon focuses on being for others what no one at her previous home church was for her: a friend.

“New people should have a guide who partners with them to ... make them feel welcome and like they belong,” she adds.

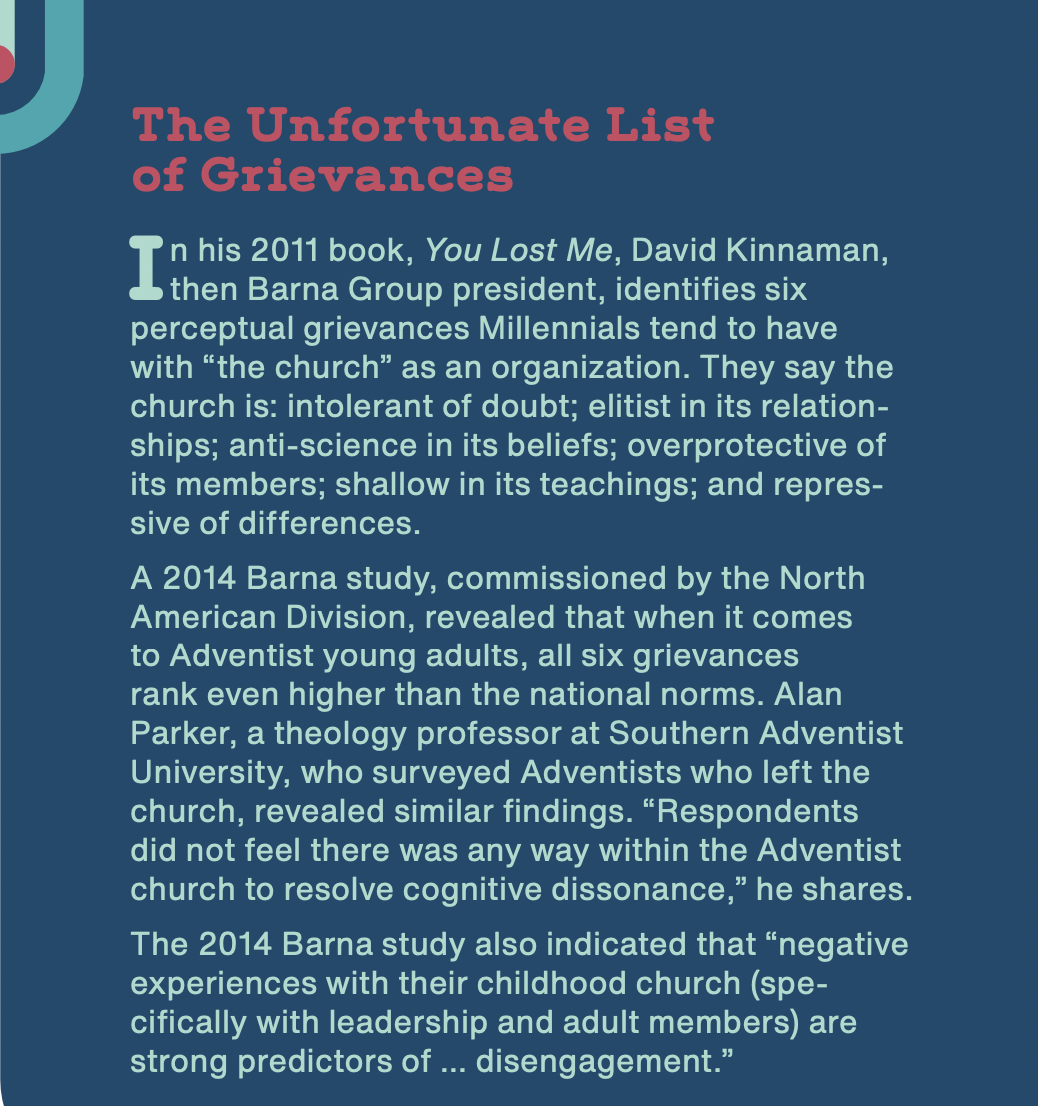

Rondon is among those who say they’ve been injured by the church’s perceived lack of compassion and justice. Alan Parker, a theology professor at Southern Adventist University (Tenn.), recently conducted a survey on why people leave Adventism, receiving more than 700 responses, nearly all of which were from Millennials. He says that 25 percent of those surveyed cited the above reasons for leaving.

'I Would Return If ...'

Adopted by a second-generation Adventist family in New York City, Joe McKenzie was baptized around 9 years old. As he grew older, McKenzie had deep questions, unable to come to grips with what he saw as a history of racism within the church—something he says many Christian denominations in the United States have in common.

The final straw was when he was fired from a church organization for having a child out of wedlock. “They pulled out the church doctrine, manual and employee handbook,” he recalls. “They quoted the Bible at me and said I’d violated a commandment and had to go. A ‘real’ church would have said, ‘You sinned, you’re forgiven, let’s see how we can work with you.’”

At this point in his journey, McKenzie has determined God does not exist. Notwithstanding this, he says there is one single thing the church could do to make him interested in being part of what they’re doing: turn their churches into community centers. If the buildings used for worship also or instead had free aid, treatment, counseling and health care centers, McKenzie would be there in a heartbeat.

“I would volunteer,” he says adamantly. “I would be a member, and I would be a major participating force with my money and my services if the church would transcend cultural norms to address the ills of society. That’s the kind of church I’d want to be a part of.”

Like McKenzie, many people who have left the church aren’t looking for entertainment. What they’re really looking for, Parker says, is community and purpose.

“They don’t just want to join the church that’s ‘feel-good;’ they want to believe that this is real and it actually changes people’s lives,” he says.

“A very significant factor in people leaving the church is how the church relates to social issues such as race and LGBTQ+,” Parker shares. The number one response to Parker’s survey question “What might bring you back to the church?” was “If the church cared about social issues.”

Religion Over Relationship

Religion Over Relationship

Bryan Reid grew up in Jamaica, attending an Adventist church in Kingston from the time he was 7 years old. Baptized at the age of 8, Reid remained active in the church throughout his youth, serving in several capacities at his local church, and eventually attending Northern Caribbean University (NCU) in Jamaica. This was where Reid’s spiritual journey began to include more questions than answers.

“I struggled financially, and it didn’t seem right that if God truly wanted me there, that He wouldn’t provide the means for me,” Reid says. He also adds that he felt uncomfortable with the heavy vetting to which theology student sermons were submitted.

Reid left NCU without graduating and immigrated to the U.S., eventually earning a Master of Divinity from the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary on the campus of Andrews University (Mich.). Though he graduated with a 3.9 GPA, he received no calls. A conversation with his advisor left Reid feeling as though his status as a single, divorced father was somehow excluding him from consideration as a pastoral leader. “I felt very discriminated against,” Reid admits.

What finally pushed Reid away was finding, after extensive research, that he disagreed with many, if not most, of the church’s teachings. When he decided to share his misgivings about Adventism with a childhood friend, the result was a fractured friendship.

“He told me he could no longer call me a brother because I had denied the teachings of Adventism,” Reid recalls. “Religiosity went above relationships.”

The Impact of Walking Away

The Impact of Walking Away

Many Christians—including Adventists—frequently wonder how to be friends with those who live and believe differently than they do. K’dee Crews, licensed clinical psychologist and an Adventist living in California, says an easy answer is “to learn from and be like Jesus,” who regularly spent time with “sinners.”

She points out, “That response of ‘we can’t have a relationship anymore’ comes from a place of fear. We’re afraid of being contaminated, and we think it’s a positive thing to not be friends with someone who turns their back on God or the church, but that’s not what God Himself does, so that doesn’t make sense at all.”

Following Christ’s example of how to engage with unbelievers or those with doubts, Andrea Jakobsons, lead pastor of Ohio Conference’s Kettering Church, chooses time and attention over judgment or condemnation.

“I still love them,” she says. “I still walk with them. I don’t just care about them when they make choices I agree with; God pursues every single one of us and desires us to be part of His family, so in my own imperfect way, I strive to show the beautiful character of God whenever possible.”

Though we may worry about how we will be impacted by loved ones walking away from the church, something to keep in mind is the impact such a decision has on the individual making it. Crews says this depends heavily on who the person is and what their experience of Adventism is. Someone who is new to the faith will have a different experience than someone who grew up Adventist, and someone who is simply leaving a set of beliefs will experience things differently than someone who is walking away from a culture. How they’re leaving plays a role, as well, Crews adds; was there upheaval or abuse or a sense of injustice?

“Someone who is simply abandoning a set of beliefs may actually feel empowered, especially if they are leaving an environment they believe is wrong in order to go fight for justice,” Crews says. “They have the comfort of still being attached to God but divorcing a belief system they don’t agree with, gaining a sense of purpose in the process.”

On the other hand, someone who is embedded in the culture of Adventism may be losing an element of their identity when they walk away, particularly if they were raised believing the church is a movement.

“This individual may experience significant unpleasant emotions,” Crews states, “possibly even depression and a sense of confusion. They’re leaving the bubble they’ve grown up with, and are losing connection, community and identity.”

A Google search for “top five stressors in life” reveals the following: death of a loved one, divorce, moving, major illness or injury, and job loss. As Crews points out, grief is involved in all of these.

“Each of these top stressors indicates a loss of something of value, which leads to grief, and then an adjustment to a new life,” she expounds. “Religious deconversion, deconstruction and leaving church” can also carry an element of guilt, she adds.

Reflecting God's Character

Deconstruction is a natural stage of development. During the fourth stage of James Fowler’s Stages of Faith, which usually begins during one’s young adult years, Fowler, who is regarded as a seminal figure in the field of developmental psychology, says, “People begin to critically examine and question their beliefs, often becoming disillusioned with their religious traditions.”

Parker has seen this countless times, both firsthand and revealed in his survey. “People want to understand what their religion really means and how they relate to the beliefs which have been handed down to them.”

As they explore their questions, less of what they thought they knew seems to make sense as they interact with other worldviews and learn different perspectives. And it would seem, Parker says, “We haven’t been great at helping our young people find faith in the midst of their doubt.”

So, how do we do better at providing positive church experiences? The short answer is to build communities that reflect God’s character and reveal the fruits of the Spirit, says Crews. “Some of the key aspects of healthy, safe religious communities are independence, free will choice, understanding, open-mindedness, flexibility in thought and diversity.”

In a 2009 interview with Ministry magazine. Roger Dudley, Adventist theologian and professor, shares, “We have to make the religious experience a good, happy, joyful one, and … finding tasks where they can use their various gifts is really important. If someone feels a place really needs them, they will stay.”

Safe Spaces

Parker points out there is no formula or road map to how individuals experience the church, so it’s important to take time and understand what’s driving the disconnection. Frequently, a painful experience within the church will lead individuals to not only doubt the organization, but God. They want a safe space to process their hurt and anger, and to know there still are safe places and safe people within the church.

According to his survey, “the three primary reasons young people leave the church are doubt, disconnection and disillusionment,” Parker explains.

There is, of course, no way to know what someone who is considering leaving the church is experiencing, nor therefore how we can address the issue, except to ask them, and then listen.

Perhaps the most powerful component of being able to walk alongside someone, Jakobsons says, is prayer, asking God to help and allowing the Holy Spirit to guide our response.

“Spending time on my knees for those people is the most important thing I can do,” she explains. “I can’t actually change someone’s mind or heart; only the Holy Spirit can do that. God has called me to keep pointing to Jesus, which means walking with those who are struggling, loving them, praying for them, letting them choose their own way and leaving the rest in God’s hands.”

‘This Isn’t Just Research’

The good news, Parker says, is that the current generation of youth, Generation Z, and their younger sibling, Generation Alpha, seem much more open to religion and church as an organization than their predecessors. In fact, the Barna Group refers to this generation as the “Open Gen.”

However, Parker admits, this openness may be temporary. “As they move into their young adult years, if we haven’t fixed the challenges we’ve had with Millennials, it will just repeat itself.”

The churches that have been most successful in bringing people back and keeping them there are authentic congregations, Parker says, who have community, mission and purpose, and know how to share that with members.

“This isn’t just research,” Parker adds; “it’s real people going through an important journey of faith. We need to remember that and do something other than just study and read about it.”

All Things Take Time

Sigamoney is grateful for what she calls her “beautiful journey,” which she says is always evolving. “It has changed a lot over time,” she comments, “but it has only deepened my love for God and for others.”

Sigamoney does envision herself returning to the Adventist church. “I really hope and pray I will find myself sitting back in Adventist pews,” she says, “I am Adventist. The core of who I am is Adventist, and it’s deeply ingrained and important to me.”

Read the November/December 2024 Visitor here!

Read the November/December 2024 Visitor here!

- Unmapped: Doubt, Disconnection and Disillusionment

- Editorial: The Pew-Filling Formula

- How to Reach Those Who Have Walked Away

- 5 Ways to Celebrate the Season Economically

- What We Need to Know About Generation Z

- Load the Ark Game Connects Faith Through Play

- Adventist Young Professionals Unite for Mission Trip to Maryland

- Do You Know the Biblical Tests of a Prophet?

- Read Our News in Spanish

Add new comment