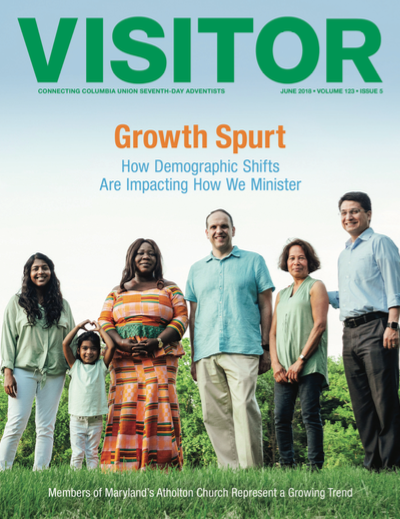

Growth Spurt: How Demographic Shifts Are Impacting How We Minister

Story by Edwin Manuel Garcia/ Images by Brian Tagalog, Kristi Rutt, Marving Alegria, Goodness Mcfiberesima/Beth Villanueva and Tracey Brown

Story by Edwin Manuel Garcia/ Images by Brian Tagalog, Kristi Rutt, Marving Alegria, Goodness Mcfiberesima/Beth Villanueva and Tracey Brown

The picturesque Lehigh Valley region of Pennsylvania, where Charles Rutt (pictured right, with Thomas Makini) has worshiped for most of his life, had enjoyed a strong Adventist presence for decades. In fact, in the 1960s, his Bethlehem Seventh-day Adventist Church outgrew itself and spawned two more congregations.

But by the late 1990s, most of the members had disappeared from his beloved Pennsylvania Conference church. “All the people I had grown up with were dying off, and the church was basically praying that something would happen, that someone would come in and we would get some new life,” says Rutt, a 67-year-old retired Adventist educator.

Their prayers were answered.

In the past 10-plus years, a stream of Adventists from Kenya joined what had been an all-Caucasian church and populated the vast majority of the once-empty pews with lively, young families. They also brought a more upbeat worship style to the platform, introduced new foods at potlucks and generated spirited church-board-level discussions about cultural/religious issues.

The church now also shares the space with a Spanish-language group that meets in the afternoon.

What the Bethlehem church experienced is becoming more common across the Columbia Union Conference, where congregations, large and small, rural and urban, are learning how to navigate into their future by embracing rapidly changing demographics.

In the short term, thanks largely to immigration of Adventists from other parts of the world, there’s been a 2.5 percent annual membership growth rate in North America. The emerging population of refugees and immigrants from many places around the globe are a boon to the Adventist Church here, which, in 2014, Pew Research Center identi ed as the most racially and ethnically diverse U.S. religious group.

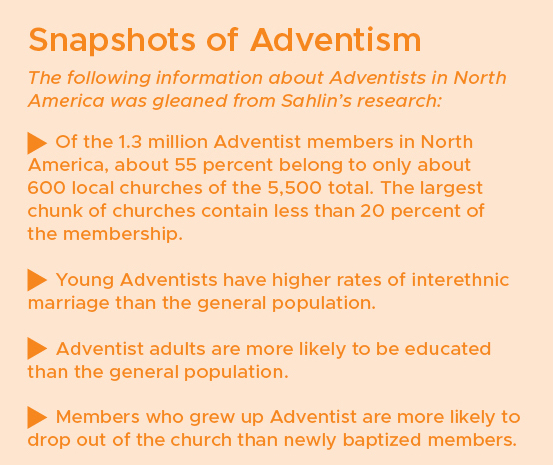

“The Adventist Church is no longer a majority white church; it’s a multiethnic, very diverse church,” says Monte Sahlin, a former Columbia Union Conference vice president and longtime Adventist researcher. A groundbreaking survey he conducted in 2008 for the North American Division also con rmed that Adventism is not only browning but also graying. “There are fewer and fewer white, young people,” Sahlin says. “The Adventist population under 18 is about 60 percent ethnic minorities.”

This demographic shift has caught the attention of some church leaders who wonder if Adventist churches in cities such as Bethlehem can meet the needs of the majority population and immigrants in the territory. For example, Kenyans now comprise about 75 percent of the church membership in a city of 75,000 that is roughly 61 percent Caucasian, 28 percent Hispanic, six percent African/ African-American/Caribbean and nearly three percent Asian.

They point to Great Britain, where immigrant-fueled growth has completely transformed the face of the church; the vast majority of the members in London are black, yet more than 70 percent of the city population is white—and are not joining the church.

If the church in North America doesn’t look at this shift strategically, how will we fulfilll the gospel commission among current and future generations? asks Gary Gibbs, who became president of the Pennsylvania Conference a year ago. “How will we effectively minister to the spiritual needs of every segment of the population of our territory?”

The Learning Curve

At the churches in Bethlehem and nearby Allentown, in an area known for a colonial industrial past and its Moravian founders, the demographic change has been welcomed, yet it’s taken some adjusting for the few remaining Caucasian families.

Self-proclaimed sticklers for punctuality, Charles Rutt and his wife, Barbara, fondly remember when programs would start on time and end on time. They don’t complain, though. “The young families have brought new life,” Rutt says, “and that has been very beneficial.”

For the newcomers, stepping into Adventist church culture in America has also been a learning experience, says Thomas Makini, a church elder and father of four girls. He and his wife moved from Kenya to New Jersey and then to Bethlehem 10 years ago because it was near Adventist schools and was a good place to raise a family.

He recalls when he realized that certain mannerisms, such as the level and tone of his voice, could unnerve people who thought he was yelling. “We didn’t know that a small thing like that can offend somebody,” he says.

Then there was the Christmas tree situation. In Kenya, Makini says Adventist churches recognize Christmas “in passing,” but it’s not typically celebrated. Yet the Bethlehem church had enjoyed a long tradition to mark the holiday each December by placing a tree on the platform. The Kenyans, though, objected. Both groups held firm to their beliefs about why the tree should or shouldn’t be in church.

After much discussion, members decided that the annual tree would be replaced by poinsettias.

Making Room for Growth

After 70 years in existence, regional conferences are experiencing profound changes, too. Some years ago, the Allegheny East Conference changed its mission statement to “Te Ethnae,” which means “to all people groups” and now includes thriving Spanish, French, Indonesian and Korean-speaking congregations.

And, just five years ago, the Allegheny West Conference (AWC) had eight multicultural congregations. Today there are 28, including ve Hispanic churches ourishing in the Cincinnati area. One of the most thriving congregations, called La Esperanza, or, “The Hope,” started four years ago with one family meeting in a house. Today the church claims more than 100 members, mostly from Guatemala, and has its own building.

“The Hispanics are bringing their enthusiasm and hardworking spirit, and that is contagious for the English-speaking churches,” says Sergio Romero, AWC’s Multicultural Ministries director.

AWC’s Central church in Columbus, Ohio, houses a Spanish-language congregation and an African-American congregation under one roof, with noontime Sabbath worship services in two parts of the building. To help introduce the multicultural congregation to the immediate neighborhood, members canvassed the streets with fliers in English and Spanish, inviting families for free burgers, bounce houses and face painting in the church parking lot.

A little more than two hours away, another AWC church is facing its future by intentionally taking measures to lower its membership age to ensure that the congregation avoids extinction. Pastor MyRon Edmonds (pictured speaking) and members moved the former Glenville church from Cleveland to nearby Euclid, Ohio, and changed the name to Grace Community church. They did so to prioritize the needs of a multicultural, under-served community whose population of 48,000 is about 60 percent black and 37 percent white.

A little more than two hours away, another AWC church is facing its future by intentionally taking measures to lower its membership age to ensure that the congregation avoids extinction. Pastor MyRon Edmonds (pictured speaking) and members moved the former Glenville church from Cleveland to nearby Euclid, Ohio, and changed the name to Grace Community church. They did so to prioritize the needs of a multicultural, under-served community whose population of 48,000 is about 60 percent black and 37 percent white.

They host a kids’ church three times a month and keep the focus outward—by feeding homeless people and holding an evangelistic-style service each week. Plans include refurbishing an old Kmart building, starting a school to serve grades nine through the first two years of college and continuing to enjoy a strong YouTube presence. Edmonds says YouTube has already drawn young converts who moved from far-away cities to join the congregation, comprised of mostly single-parent Generation Xers and Millennials.

Edmonds states attendance is growing due to a lot of children and teens from the community. “I think it’s important that people understand that the foundation of what we’re doing is the Bible and the Spirit of Prophecy,” he says. “We’re not just trying to be cool and cutting edge because it’s 2018.”

Some churches in the Columbia Union are realizing that successful ministry in a time of shifting demographics means offering different programming to parents and their children.

In the Potomac Conference, for example, many children of Central American immigrants, who settled in and around the District of Columbia during the past two decades, are proud of their cultural roots, yet aren’t embracing their parents’ native Spanish. Having been born in the U.S., English comes more natural to them.

The church’s solution: congregations, such as the Arise Hispanic-American church in Silver Spring, Md., cater to second-and third-generation Latinos with sermons, Bible study and socialization in English.

Other churches are trying to move in a similar direction.

Williams Ovalle, pastor of the Manassas Spanish church and the Manassas II Spanish Company, both in Northern Virginia, dreams of offering his second- and third-generation youth their own church with English programming, because many of the young members, he says, “live between two worlds” and “church doesn’t necessarily ll their needs.” As a result, the youth abandon the church, or attend, but don’t pay attention.

because many of the young members, he says, “live between two worlds” and “church doesn’t necessarily ll their needs.” As a result, the youth abandon the church, or attend, but don’t pay attention.

His vision has been met with resistance by parents and even church board members who insist children must be taught in Spanish.

Caption: Worship director Carlos Paz (pictured left) and Pastor Williams Ovalle (right) minister to and with second- and third-generation Latino members like Jasmin Guevara and Saraí del Cid at the Manassas Spanish and Manassas II Spanish churches in Northern Virginia.

After receiving permission from the church boards in his pastoral district, which also includes the Reston and Centerville (Va.) churches, Ovalle started the monthly English service, which the youth loved. However, when word got back to church leaders that the youth were singing worship songs that weren’t from the hymnal, the permission was rescinded, he says.

Eventually the boards relented, and about 80 youth, ages 12-22, now meet at a Manassas community center every third Sabbath.

“I just hope that I can help create a safe environment to help young people connect with God, not feel judged and have a relationship with Jesus,” Ovalle says. “That’s all we’re trying to achieve.”

Breaking Language Barriers

In the New Jersey Conference, meanwhile, the First Bilingual church in Middlesex has found its own best practice of including Spanish- and English-speaking worshipers: the church’s three interpreters translate every announcement, prayer, testimony and sermon. Worship songs alternate, one English, one Spanish.

In neighb oring Philadelphia, Boulevard church interpreters (Olena and Myron Androshchuk pictured) help translate a sermon into Ukranian for other members of the Boulevard church translate sermons into Swahili and Ukranian, beamed into headphones on congregants’ ears. Members of Italian and German heritage first populated the Pennsylvania Conference church, which opened in 1955. Later, Pastor Buddy Goodwin says refugees arrived from the Congo, then members from the Caribbean islands and then people from Eastern Europe.

oring Philadelphia, Boulevard church interpreters (Olena and Myron Androshchuk pictured) help translate a sermon into Ukranian for other members of the Boulevard church translate sermons into Swahili and Ukranian, beamed into headphones on congregants’ ears. Members of Italian and German heritage first populated the Pennsylvania Conference church, which opened in 1955. Later, Pastor Buddy Goodwin says refugees arrived from the Congo, then members from the Caribbean islands and then people from Eastern Europe.

“Every day it is an opportunity to see how God is working to pull His people together because we deal with so many diverse groups of people in one local setting,” Goodwin says.

The Ohio Conference has undergone significant change in recent years in areas that for the longest time were majority Caucasian, which has prompted some Adventists to experience learn-as-you-go cultural education.

The population at the Worthington church (some members pictured below), just outside Columbus, which was nearly all Caucasian around the year 2000, has dipped to about 50 percent, with people from 32 nations lling the rest of the congregation.

On numerous occasions, lead pastor Yuliyan Filipov, who was born in Bulgaria and speaks several languages, has stepped in and helped people of different ethnic origins to better understand each other’s culture.

Of note was a memorial service held in the Nigerian tradition, which started in the sanctuary in the after-noon and ended in the gym at 4 a.m. Prior to the service, Filipov advised the African families not to be offended if Caucasian families left the program before it ended, because they’re not accustomed to staying that long at a memorial servi ce.

ce.

“Having diversity makes the church vibrant,” Filipov says, and it serves as an evangelism tool. “It gives the church a avor that makes it palpable to people who are not related to Adventism.”

Some schools in Ohio are seeing a surge in diversity, in part because of refugee resettlement. Two schools on opposite ends of the state—Mayfair Christian School in Akron and Spring Valley Academy in Centerville—have upwards of 80 students from refugee families, says Richard Bianco, the Ohio Conference superintendent of Education.

The growth also is attributed to the state’s voucher law, which has made Adventist education more accessible to families of color.

In other regions, including those near the District of Columbia, institutions like Adventist HealthCare have experienced diversity up-close for years.

The integrated network of hospitals and other healthcare facilities serves Montgomery County, Maryland, where more than 50 percent of the population of a million people identifies with an ethnic or racial minority group. Based on its Community Health Needs Assessments and the changing patient population, the health system has implemented a number of programs and services to spread the message of good health and promote health equity.

The integrated network of hospitals and other healthcare facilities serves Montgomery County, Maryland, where more than 50 percent of the population of a million people identifies with an ethnic or racial minority group. Based on its Community Health Needs Assessments and the changing patient population, the health system has implemented a number of programs and services to spread the message of good health and promote health equity.

Among the more significant activities at the Adventist HealthCare Center for Health Equity & Wellness are partnerships with safety-net clinics, a robust diabetes self-management education program and cultural competency training for staff. In addition, the Center has trained qualified bilingual staff interpreters across the system, and their number has more than tripled since the program began.

Multiculturalism has also been a mainstay at several Chesapeake Conference churches, and pastors there say that having an open mind and being good listeners is essential for avoiding the kind of cultural clashes that can otherwise tear apart a congregation.

The administration plans to start tracking demographic information voluntarily offered by members, to ensure that its churches are reaching every segment of their community, says Shawn Paris, pastor of the Atholton church (some members pictured below) in Columbia, Md., whose 600 members are comprised of 68 nationalities.

When Paris first arrived at Atholton, a couple of members gave him a stark warning about a new group of worshipers they thought would “take over” the church.

When Paris first arrived at Atholton, a couple of members gave him a stark warning about a new group of worshipers they thought would “take over” the church.

Five years in, Paris has not found that to be the case.

“On a regular basis from the pulpit, we talk about how we love our diversity,” he says. “We made a conscious choice that this is who we are.”

Other pastors have been pushed into the role of mediator at fellowship luncheons, listening to immigrants explain that it was acceptable to eat fish or chicken at potluck in their country of origin, while also hearing from longtime American Adventists who prefer vegetarian fare at the buffet table.

Waldorf (Md.) church Pastor Dan Darrikhuma, whose congregation has shifted from 90 percent white to less than 10 percent in the past 15 years in a community that is 53 percent black and 35 percent white, encourages members to move out of their comfort zones and get to know each other better. “One of the things I’ve asked members to do is to be intentional to invite [other members] to lunch or to sit with them in potluck,” Darrikhuma says. “Sometimes it takes a little educating and reducing fear.”

Mike Speegle, senior pastor of the New Hope church in Fulton, Md., believes churches in the Columbia Union should think intentionally about how to reach their communities, with an eye toward with whom we are going to spend eternity.

“You go from D.C., to Baltimore, to Philadelphia, to New Jersey and Ohio, a lot of that has a rich multi-ethnic makeup; it’s part of who the community is,” he says, “and the community we will ultimately live in.”

Read these stories from the June 2018 Visitor:

Read these stories from the June 2018 Visitor:

- Feature: Growth Spurt

- Editorial: Master, Don't You Care?

- Book Release: Praying God's Heart

- Book Release: Walk the Pathway of Prayer

Add new comment