Archaeologists Uncover Clues About Women in Early Christianity

In 2014 an archaeological team from Andrews University (Mich.) began excavating a fourth-century funerary basilica and its surrounding settlement known as San Miceli (WATCH VIDEO HERE). The goal was to investigate the emergence of Christianity in late antiquity. The site, located in Salemi, on the west side of Sicily (Southern Italy), preserves the remains of one of the earliest known Christian churches (left) and was first discovered by archaeologist Antonino Salinas in 1893. During the last five years, the university team (below) has uncovered three different periods of occupation of the church building (fourth to sixth centuries); a baptistry; a surrounding cemetery (necropolis); and an adjacent rustic villa. While reviewing previous excavation reports, they noticed something especially interesting about Tomb 54.

In 2014 an archaeological team from Andrews University (Mich.) began excavating a fourth-century funerary basilica and its surrounding settlement known as San Miceli (WATCH VIDEO HERE). The goal was to investigate the emergence of Christianity in late antiquity. The site, located in Salemi, on the west side of Sicily (Southern Italy), preserves the remains of one of the earliest known Christian churches (left) and was first discovered by archaeologist Antonino Salinas in 1893. During the last five years, the university team (below) has uncovered three different periods of occupation of the church building (fourth to sixth centuries); a baptistry; a surrounding cemetery (necropolis); and an adjacent rustic villa. While reviewing previous excavation reports, they noticed something especially interesting about Tomb 54.

Tomb 54 is located in front of the altar, beside a priest’s tomb, inside the San Miceli Basilica. This was unusual as burials in front of the altar are typically reserved for religious leaders. Inside this tomb archaeologists found a woman’s burial place. The mosaic covering the tomb was destroyed, obliterating her identity, but her jewelry with religious symbolism and bones were found intact. The defacing of her identity was not motivated by theft, otherwise there would be no jewelry and the bones would have been disturbed. The location of her burial and the religious artifacts likely mean that she was a wealthy patron or leader of the church.

Since working at the dig site, Andrews University archaeologists have uncovered the graves of numerous other women around the basilica. This is understandable because Christianity grew faster among women in the Greco-Roman era so there were more women than men in the Early Church. In addition, wealthy women were expected to help the less privileged. Such female patronage was honored at the time of the patrons’ burial. The patronage system continued when they converted to Christianity. The Early Church generally met in houses, and since the home was typically maintained by the wives, it meant these gatherings were within the female social domain. They financially supported the church, opened their homes to be used as gathering places by the Christian community, and upon their death, donated their property for its continued use. In the fourth century when Constantine sanctioned Christianity, many of these homes were rebuilt and enlarged for use as basilicas. There is evidence this may have been the case at San Miceli. In addition, there are an unusual number of female saints in Sicily, indicating how important women were to the Sicilian Christian church.

The findings at San Miceli compelled Andrews University archaeologists to research women’s participation in the surrounding regions to help interpret the data being uncovered in the excavations. To date we have compiled a number of archaeological artifacts as well as literary references that shed light on this subject.

KALE PRESBYTER

In the Roman town of Centuripae, located on the east side of the island of Sicily, archaeologists found a tombstone of a woman named Kale (Watch video) who lived in the fourth to fifth century. The tombstone, translated from its Greek inscription, says, “Here lies the presbyter Kale who lived 50 years without reproach (amemptos). Her life ended on 14 September.” At present, this tombstone (left) is part of an exhibition at the Antonino Salinas Archaeological Museum in Palermo, Sicily. Her title, presbyter, means elder or minister, indicating she was a church leader. The Greek word, amemptos, which means blameless or without reproach, was frequently used in connection with church officers in Sicilian literature.

LETA PRESBYTERA

In the Southern Italian region of Calabria, in the early Christian town of Brutium (modern Tropea), archaeologists found the tombstone honoring the memory of a woman named Leta who also lived in the fourth to fifth century. The Latin inscription on her tombstone reads: “Sacred in happy memory: The presbytera Leta, who lived forty years, eight months, and nine days, whose husband erected this tombstone. She went forth in peace on the day before the Ides of May (15 May).” New Testament scholar and author Ute E. Eisen notes that references to church organization in Tropea are “especially sparse,” and only three individuals who were church office holders are thus far attested, Leta being one.

BITALIA AND CERULA

In the northern part of Naples, Italy, the Catacomb of San Gennaro started as a pagan  burial place in the second century, and Christians began to use it around the third century. Over a 300-year period, as the church grew, they placed the remains of many local bishops and believers there. Like other early Christian catacombs, San Gennaro (Watch video tour) was decorated with frescoes and mosaics, some of which still remain visible on its walls and ceilings. In 2009 researchers found frescos portraying Bitalia and Cerula (right).

burial place in the second century, and Christians began to use it around the third century. Over a 300-year period, as the church grew, they placed the remains of many local bishops and believers there. Like other early Christian catacombs, San Gennaro (Watch video tour) was decorated with frescoes and mosaics, some of which still remain visible on its walls and ceilings. In 2009 researchers found frescos portraying Bitalia and Cerula (right).

Each woman is shown with open arms and raised hands in a prayer-like position, a very common depiction in early Christian iconography. They are also presented with the “Chi-Rho” symbol (the first two Greek letters of the name “Christos” or Christ) above their heads. Cerula’s fresco is in better shape, and also includes the Greek letters Alpha and Omega (the beginning and the end). Another fresco at San Gennaro, a martyred male bishop, displayed in the same catacomb, also features this symbol above his head. These are the only two times this symbol is used in this catacomb.

What makes the women’s frescoes especially noteworthy is that in each of them, open books appear above both sides of their heads. The names of the Gospels—Mark, John, Luke, Matthew—are written on the pages of the books.

Also important is the fact that surrounding the Gospel books are tongues of fire. The Apostolic Constitutions, a fourth-century manual for clergy, describes the procedure for ordaining bishops. It says that the open Gospels should be held bydeacons over the head of the candidate. Other literary references of the same time period also mention this process, indicating its common practice. In addition, Palladius, the first Christian bishop of Ireland, wrote in AD 430 that the tongues of fire were a symbol of the descent of the Holy Spirit on the candidate, like the descent of the Holy Spirit on the apostles at Pentecost. Thus, the Gospels over the head of a person are a sign of the ordination of a bishop by the church, and the tongues of fire symbolize ordination by the Holy Spirit.

LADY BISHOP Q

North of Rome in the city of Umbria, researchers found and catalogued a fifth- to sixth-century marble tombstone of a woman. The marble is damaged, which makes the text of the first line uncertain. However, the Latin inscription on the second line reads, “Here rests the venerable woman bishop Q … interred in peace … .” Although this could be interpreted as the wife of a bishop, there is no reference to a husband, and the Latin interpretation used, “fem episcopa,” is “woman bishop.”

WOMEN RELIGIOUS TEACHERS

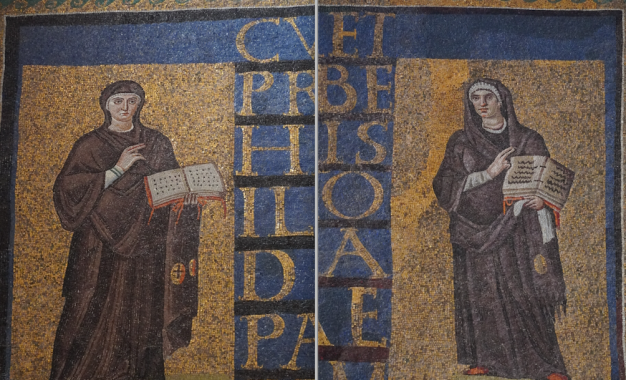

In the fifth century, the priest Peter Illyria built the Santa Sabina Basilica in Rome over a former house church (WATCH video tour). Above the door of the main entrance there is a mosaic portraying two women (above): one is identified as representing the church of the circumcised and the other as representing the church of the Gentiles. Both are portrayed with the familiar hand gestures displayed by religious teachers of that era and hold a large open book (likely the Bible). Such iconography was typically used to identify bishops. In addition, the woman representing the church of the Gentiles holds a cloth over her left arm, which only priests used when serving the eucharist.

THEODORA

In the ninth century, one of Rome’s churches was St. Prassede (See video), a basilica built over a former house church site. Pope Paschal I restored the church and added the chapel of St. Zeno, which he decorated with beautiful mosaics. These mosaics portray a number of people, some of whom are identified. The name of Pope Paschal I’s mother, Theodora, was written in the mosaics in this chapel by her portrait, followed by the title, episcopa. While an exact meaning cannot be determined, this title typically referred to the office of bishop.

LITERARY MENTIONS

In addition to the above archaeological artifacts mentioned, a few literary confirmations of women participating in leadership roles in early Christianity come from male references:

In AD 494, a letter from Pope Gelasius I states: “To all episcopates [bishops] established in Lucania [modern Basilicata], Bruttium [modern Calabria], and Sicilia [modern Sicily]: ‘Nevertheless we have heard to our annoyance that divine affairs have come to such a low state that women are encouraged to officiate at the sacred altars and to take part in all matters imputed to the offices of the male sex, to which they [women] do not belong.’”

In the 10th century, Bishop Atto (AD 885–961) of Vercelli (North Italy), reflecting on ancient church history, mentions that women, of necessity, exercised various ecclesial leadership roles in previous centuries: “In the primitive Church … many are the crops and few the laborers, for the helping of men, even religious women were ordained caretakers in the holy Church. … Not only men but also women presided over the churches because of their great usefulness … female presbyters assumed the office of preaching, leading, and teaching, so female deacons had taken up the office of ministry and of baptizing, a custom that no longer is expedient.”

FACTS AND ARTIFACTS

Information on this topic has been found in various countries around the Mediterranean basin including Italy, Turkey, Israel, France, Croatia, Greece, Egypt, Algeria and others. Beyond what is shared here, there are many other archaeological and textual references about the leadership roles of women in the early spread of Christianity that could be discussed, and more will be discovered.

People may debate exactly what these women did—and whether it was appropriate—but the historical facts and artifacts do indeed testify that women assumed leadership roles at virtually all levels of the church during the early centuries of Christianity. And while what happened in the past should not necessarily determine what should occur today, this information can contribute to a more informed discussion and growing body of knowledge. How women disappeared from leadership roles in the later centuries is also an interesting question worthy of future study.

Carina O. Prestes is a doctoral candidate in Biblical Archaeology at Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Mich., and associate director of San Miceli Excavations in Sicily, Italy. She’s currently researching archaeology of the New Testament and early Christianity.

Read and share these articles from the November/December Visitor:

Read and share these articles from the November/December Visitor:

Add new comment