The Hidden Harm of Emotional Abuse

Story by Becky St. Clair and Ricardo Bacchus

He calls me useless. Lifeless. Disgusting.” Fatima* forces the words out, almost as though these insults from her husband of 30 years, who is also a church elder, cause her physical pain to repeat. She continues, “He doesn’t use my name anymore; he won’t even look at me. Recently he said,‘I can’t believe I ever loved you.’”

Fatima’s story is heartbreaking, and sadly it is not unique. Hers is an example of emotional and psychological abuse, often referred to as “the hidden abuse,” since it leaves no physical mark and is so difficult to identify.

Domestic abuse is defined by the United Nations as “a pattern of behavior in any relationship that is used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner.”1 Though most often we envision domestic abuse being physical or sexual, it can also be emotional, economical, verbal, psychological, spiritual or even reputational.

“We’re not talking about a one-time thing where someone says something they regret in a moment of anger,” explains Michelle Perez, who spent many years in a physically abusive marriage and is now a domestic abuse prevention educator in Pennsylvania who spoke at this year’s Pennsylvania Conference Camp Meeting. “We’re talking about an identifiable pattern of repeated harmful behaviors.”

Here are two real-life examples of abuse Perez has encountered.

Rosa* had no access to her husband’s primary bank account. She had no idea what his income was or what her husband was doing financially. The only money she had access to was in a separate account he had set up for her with only the money he gave her each day. Sometimes that meant nothing at all. If Rosa’s husband deemed no errands were neces- sary, he took the car keys with him when he left for the day.

Gabrielle* endured derogatory comments about her weight, skin color, hair and other physical attributes on a daily basis. Every morning, her husband forced her to do a weigh-in; if she weighed more than 137 pounds, she was not allowed to eat that day.

Perhaps one of the most extreme stories of domestic abuse survival in the church is that of Tamara Schreven, whose husband, a well-known Adventist evangelist, was severely emotion- ally and psychologically abusive.

A few weeks into their marriage, Schreven accidentally left her curling iron on. In response, her husband refused to speak to her or even acknowledge her presence for four days.

“His entire body language said, ‘You are repulsive,’” Schreven recalls. “When those days ended, he told me they were meant to teach me a lesson so I’d never do what I’d done again.”

These “silent treatments” became a common part of Schreven’s life. Often, she would have no idea what she’d done to upset him, and there was no discussing the issue. When his prescribed silent treatment period was over, he would move on as though nothing had ever happened.

“We never resolved anything, and I began to think it was all me,” Schreven recalls. “I began to believe I was the problem.”

Perez says gaslighting—a form of emotional abuse that causes a victim to question their own feelings, instincts and sanity 2—is extremely common in these situations. “You think there’s no way you saw what you saw or heard what you heard, because the other person says you didn’t,” she expounds. “You doubt yourself because this is the person you love.”

Unlike physical abuse, emotional and psychological abuse leave no visible mark, but they can be just as dangerous and physically threatening as the more obvious and recognizable forms of abuse.

When Fatima went to the doctor for heart palpitations, tests revealed her heart was only operating at 40 percent. The doctor indicated this was due to extreme stress. Schreven, too, saw her health decline while in her abusive marriage.

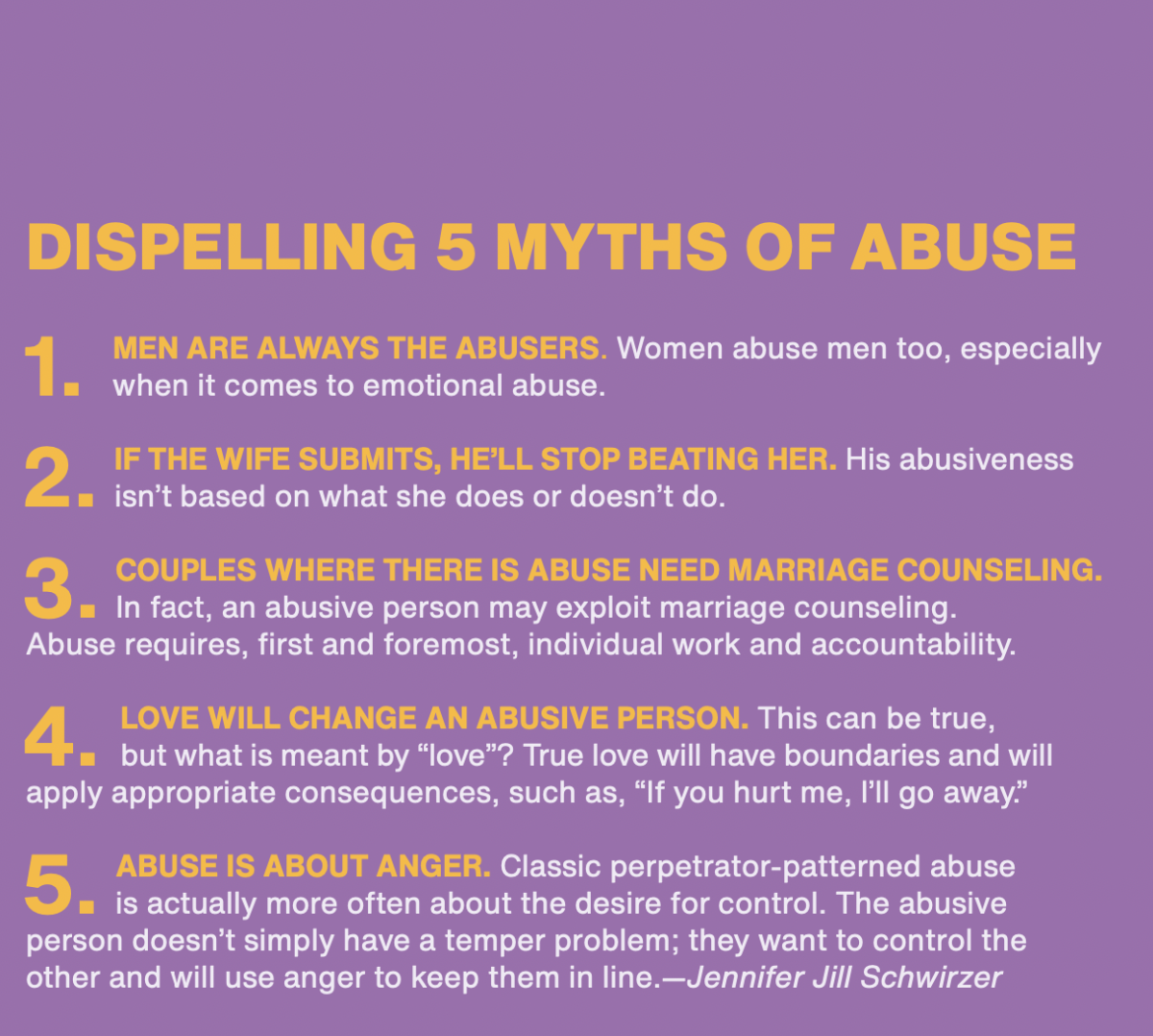

Jennifer Jill Schwirzer, an Adventist, Florida-based licensed professional counselor, author and speaker, says, "The reason people overlook emotional abuse is becuase it's not tangible, and we're including to undersestimate the importance of emotions." She quotes the singsong phrase often repeated by children: "Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me," and poins out that this is undeniably false.

"We say things like this simply because we are not trauma-informed enough to realize words and other forms of emotional abuse harm the nervous system,” she says.

Most often, Schwirzer says, shaming and contempt are typically delivered through words.

“We might wish we were impervious to shaming, but we are not, particularly from a person we’re close to,” she explains. “Shaming and contempt instill despair. Emotions are absolutely damageable.”

Through tears, Fatima agrees. “My husband has never hurt me physically, but I wish he would,” she says, her voice breaking, “because then I would have a visible reason for the pain. No one can see my pain, but I wear it, I sleep with it, I live with it.”

Children Are Affected Too

Jennifer Benavides, a social worker and an Allegheny East Conference member, recently worked with her church to host a Mental Health Awareness Week. As her primary focus is working with children, she spoke about how to recognize mental health struggles in young people.

“Kids see abuse in their lives as early as age two or three,” Benavides says. “It’s important to know the red flags, especially with those who can’t communicate with words.”

After her seminar, Benavides says she was approached by several people, some church members, who shared their own experiences with ongoing abusive situations.

“I had no idea this was happen- ing within my own church,” she says. “Abuse of any kind can be hidden very well.”

Perez says, “The first time I was asked to publicly share my story, I asked my kids how they felt about it, and they were wholly support- ive. They said, ‘Mom, stop being silent. You don’t have anything to hide.’ It’s been such a healing journey for me and my kids.”

Schreven shares, “No one should experience what I went through. I’ve never been an up-front person, but God has used my deepest pain to help me reach my highest calling. That’s a gift I want to help others receive too.”

Perez adds, “For so many years, [abuse] was a taboo subject. No one was talking about it, let alone from the pulpit. That’s my mission. To be able to educate within the Adventist community and open their minds to how this can happen in Christian homes.”

Where Can I Seek Help?

Finding and asking for help is usually not easy, even for individuals who attend church regularly and have what is expected to be a supportive community.

When Lorraine* immigrated to the United States knowing no one, her desire to integrate into the culture led her into a relationship with a man who seemed to be the perfect fit. Several years later, Lorraine married him, had a job she enjoyed, friends, and was beginning to feel at home.

That was until her husband asked her to move out of state with him and work for his company.

Lorraine quickly realized how isolating her new situation was. She knew no one outside of those she worked with at her husband’s company, and after two months, there was no longer a job for her. She spent her days at home alone, with nothing to do.

“His daughter cooks his meals, takes him to appointments, manages his bank accounts,” Lorraine says. “He tells me he doesn’t need me.”

She shares, “I talked to my pastor about what was happening, but he did nothing. He doesn’t even call to check on me. Maybe he could have introduced us to someone to talk to for counseling.”

Fatima, too, reached out to her pastor and head elder for help. Their response: “What did you do to make your husband do these things?” Next thing she knew, her story was all over the church. “I thought the church would be a safe place for me, but I despise it. I hate it.”

Even church leaders who do try to help often urge couples not to consider divorce—an approach with long-held tradition in Adventism as well as other faiths. The most oft-quoted scripture in support of this approach is Malachi 2:16, where in most English translations God says, “I hate divorce.”

Perez says, “Well, I hate divorce, too, and I went through it. But God also doesn’t want his sons and daughters controlled, demeaned, physically injured, and treated as though they are less than the family dog.”

Perez says, “Well, I hate divorce, too, and I went through it. But God also doesn’t want his sons and daughters controlled, demeaned, physically injured, and treated as though they are less than the family dog.”

Schwirzer points out that many abuse survivors have been effectively cut off from money, friends, family and other means of survival.

“The amount of support a separating or divorcing person may need can be scary to a busy pastor or church member,” Schwirzer admits. “But the same stewardship principle which leads Adventists to talk about abstaining from smoking, drinking and unhealthy food applies to our mental health too. Being around abusive people is bad for one’s health, and this must be considered.”

So how should individuals experiencing abuse seek out help?

“They need trauma-informed care, and often that is not a pastor, unless they have special training,” Perez emphasizes. “It’s just not their wheelhouse.”

Schreven says that in many cases such as her own, going to counseling as a couple—especially with a pastor—isn’t safe because the abuse can escalate.

“Narcissists are so good at putting on a facade of being very charismatic and manipulative, that they can make the church think their victim is crazy,” she says.

“In my opinion, it’s better to seek counseling alone, outside of the church, with someone who doesn’t know you.”

Perez likens seeking domestic abuse counseling from a pastor to expecting someone with no medical training to conduct surgery. She says that most pastors likely mean well in their attempts to help and are simply trying to “preserve the family unit.”

She says, however, “The prob- lem is that with that method, the message to the abused is, ‘You don’t matter’ and ‘This is your fault because your prayers haven’t fixed the other person.

Pastors may not be the resource, but they should absolutely have resources available, and that is something every church can [offer].”

And for that, they need a plan.

Perez has helped her home church create a process for when someone in an abusive situation comes to a church leader seeking advice, counseling or help. In partnership with the Family Justice Center, they created a step-by- step, scripted response plan.

“We are not mental health counselors or attorneys,” Perez emphasizes. “We are simply there to help them find the resources they need.”

*Pseudonyms

1. un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse

2. thehotline.org/resources/what-is-gaslighting

Add new comment